Rendering credits: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

Rendering credits: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

Ask an average New Yorker to name the city’s most famous hotel and they would likely point either to The Plaza on Fifth Avenue and 59th Street or to the Waldorf Astoria on Park Avenue and 50th Street. Fewer, however, may know that since 1897, the original Waldorf-Astoria (or 1893 of counting the original Waldorf) on Fifth Avenue between 33rd and 34th Streets reigned supreme among the city’s high society and well-heeled visitors alike. The once-hyphenated hotel has jockeyed with the Plaza for the title of the city’s most famous hotel ever since, even after its successor opened on Park Avenue in 1931, with an Art Deco sumptuousness that outshone the hulking extravaganza for its predecessor.

The legendary Waldorf Astoria is a crown jewel of New York’s ongoing golden era of condominium conversions stands at the corner of Park Avenue and East 50th Street, where the upper floors of the hotel are being renovated into Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, a collection of 375 opulent studio to four-bedroom apartments.

In this article:

The refurbishment is a major interior makeover that will not alter its green Mayan-style roof-top turrets nor do away from its famous lobby clock tower that was commissioned by Queen Victoria for the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago. As the development approaches its target sales date, now is a perfect time to delve into the storied history of the storied hotel and its once equally-famed predecessor, the original Waldorf-Astoria now replaced by the Empire State Building.

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Skidmore Owings and Merrill

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Skidmore Owings and Merrill

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria Credit: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria Credit: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

The original Waldorf-Astoria Hotel

The original, opulent Waldorf-Astoria on the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street has long since been replaced by the even more famous Empire State Building. Thankfully, a plethora of historic accounts has preserved the memory of the grand chateau in exquisite detail.

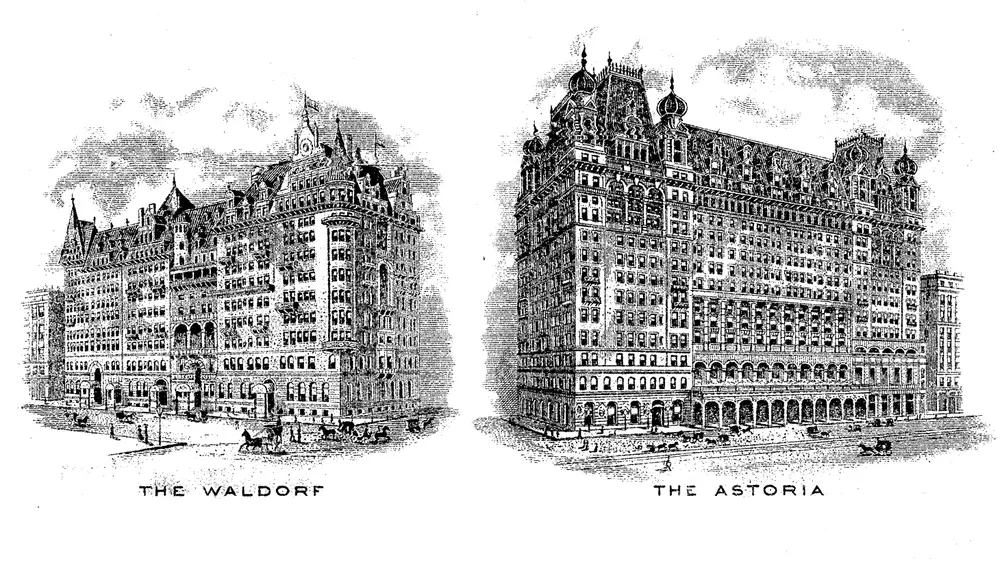

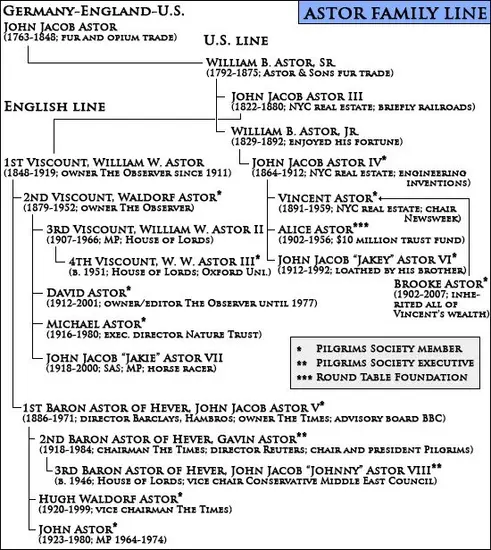

The hotel’s hyphen reflects a long and often contentious history intertwined with the Astors, one of New York’s most powerful turn-of-the-century families. The Waldorf occupied the site of John Jacob Astor's townhouse on the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street and was erected by his son, the Honorable William Waldorf Astor for George C. Boldt. The hotel, which opened for business March 14, 1893, takes its name from the little town of Waldorf in the Duchy Baden, Germany, the ancestral home of the Astor family. A picture of the town in stained glass could be found over the main entrance of the South Palm Garden on the 33rd Street side of the building.

Engraved vignettes of the original separate hotels. Credit: Wikipedia

Engraved vignettes of the original separate hotels. Credit: Wikipedia

The original Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, looking at the Astoria side. Credit: Brown Brothers, NYPL

The original Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, looking at the Astoria side. Credit: Brown Brothers, NYPL

The Astoria, which occupied the site of William B. Astor's townhouse on the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street, was erected by his son Col. John Jacob Astor for Mr. Boldt, and opened for business November 1, 1897. It is named for the town of Astoria, founded in the year 1811 by John Jacob Astor the first, at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon.

Both hotels were designed by Henry J. Hardenbergh, already notable for The Dakota and soon to be famed for the Plaza Hotel, in an exuberant German Renaissance style, with the first hotel treated as an end pavilion and the combined development containing 1,300 bedrooms and 40 public rooms.

In their great book, "New York 1900, Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890-1915," Robert A. M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin and John Massengale provide the following commentary on the family feud and its unique architectural manifestation:

"The Waldorf was built by William Waldorf Astor, who was preparing to settle in England where he could buy himself a title (he ultimately became a viscount). Astor razed his father's house on the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and Thirty-third Street and overshadowed his despised aunt's house next door on the avenue with a massive ten-story hotel crowned by turrets and enormous gables rising another three or four stories. Aunt Caroline's son, John Jacob, decided it would be fun to demolish his mother's house and build stables to stink up William's resplendent hotel. But since they were in business together - their joint fortune estimated at two hundred million dollars - John Jacob reconsidered and joined his cousin William Waldorf in the hotel business. John wanted to name his part of the hotel Schermerhorn for his mother's family, but William persuaded him to call the new, taller section the Astoria, after the dream city John Jacob I had hoped to develop in his fur-trapping empire.”

William Waldorf Astor. Credit: Wikipedia

William Waldorf Astor. Credit: Wikipedia

The Astor family tree. Credit: The Pilgrims Society

The Astor family tree. Credit: The Pilgrims Society

On Tom Miller’s great blog, Daytonian in Manhattan, the article "The Lost Waldorf-Astoria Hotel - Fifth Avenue at 33rd Street" offers further insight:

"The heated family feud between William Astor and his aunt, Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, came to a head in 1890. Living next door to her was no longer possible for William. The near-twin brownstone mansions his father, John Jacob Astor II, and his uncle, William Backhouse Astor, had built were separated by a wide common garden.... Caroline Astor reigned supreme over New York Society in the 1890s. Her mansion at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street was the scene of annual balls for three hundred or more of society's most elite....

"The 13-story hotel dwarfed Caroline Astor's venerable home and was recognized as the last word in opulence. Hardenbergh's creation has 530 rooms and 350 private bathrooms. The sumptuous public spaces were immense and of the more than $3 million total cost, $800,000 was spent on interior fixtures and furnishings.… Astor hired George C. Boldt, manager of the Bellevue and Stratford Hotels in Philadelphia, to run the Waldforf....

"Astor pulled up all the stops in decorating the interiors to guarantee that his was New York's most elegant hotel. The main entrance hall rose 21 feet and boasted Sienna marble pilasters with solid bronze capitals. Off the entrance hall was the garden court with full-grown palms and flowering plants. The German-inspired black oak-paneled cafe on this level, for men only, featured unusual lighting fixtures. 'The lights in this room will spring from stag-horn torches held by carved figures of the Tyrolerweibschen, or Tyrolean women,' said The Times....

"The main dining room was a reproduction of a great hall in the palace of King Ludwig of Bavaria....The Ladies' Drawing Room, off the dining hall, was a 'perfect reproduction of an apartment of Marie Antoinette,' said The Times....

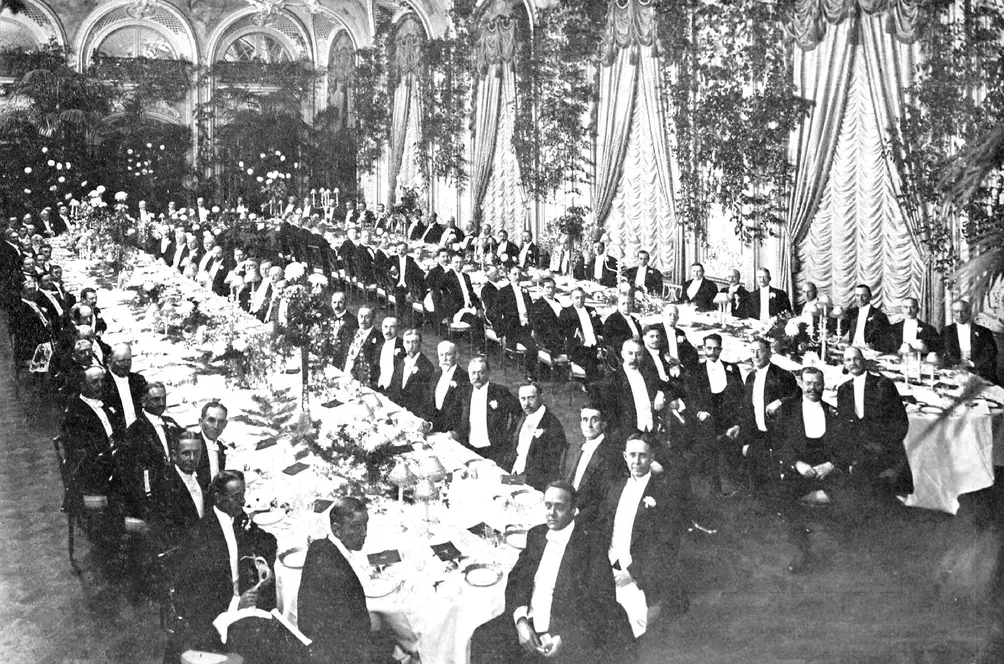

"The collaboration of two feuding cousins was a phenomenal success. The Waldorf-Astoria became synonymous with wealth and luxury in hotels. The long marble corridor that connected the two buildings earned the nickname 'Peacock Alley.…' The Waldorf-Astoria overtook Delmonico's and Sherry's as the place to entertain. And Boldt kept up with the times. He initiated Monday-morning musicales, a trend that caught on with society and he installed ping-pong tables for women when indoor tennis became the rage. He brought in telephones, dumb waiters for room service, pneumatic tubes for rapid mail delivery, and instituted the 'floor clerk.'"

The Octagon Room of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, 1893. Credit: Wikipedia

The Octagon Room of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, 1893. Credit: Wikipedia

The Elbert Henry Gary banquet at the Waldorf-Astoria, 1909. Credit: Wikipedia

The Elbert Henry Gary banquet at the Waldorf-Astoria, 1909. Credit: Wikipedia

The final product was a palace of luxury hardly matched on either side of the Atlantic Ocean. The Thirty-third Street entrance had an ornate entrance marquee with four finials and a central lantern in front of a five-step-up entrance. The 34th Street entrance was even more imposing as it was not only much longer but also deeper and was nestled beneath a long arcade of recessed arches and the ends of the building sported tall, Moorish-like turrets and many finials. A few balconies modulated the building's bulk.

The center of the main lobby was highlighted by a large clock that had been commissioned by Queen Victoria for the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago. Its four faces showed the time in New York, Madrid, Tokyo and Constantinople and the ornate piece was topped with a miniature of the Statue of Liberty.

The second Waldorf-Astoria Hotel

The volatile and ephemeral tastes of the high society change as rapidly as the elites change their wardrobes. The hotel that was the last word in societal fashion in 1897 was already considered staid and passe by the first decades of the 20th century, especially when the crisper, airier, green-and-white visage of the Plaza Hotel made the stalward Waldorf-Astoria look like a cumbersome, Old World pile of heavy ornament and dour futnishings that would not compete with the Plaza’s top-of-the-line tech marvels such as in-unit thermostats.

By the 1920’s, just as a stock market craze gripped the nation, New York caught the skyscraper fever, with developers literally racing against time and against one another to build the tallest, the largest, and the most splendid towers. On May 3, 1929, the Waldorf-Astoria closed its doors and was demolished shortly afterward to make way for the Empire State Building, which would reign as the world’s tallest freestanding structure from 1931 to 1967, when it was surpassed by the Ostankino Tower in Moscow; in 1970, the North Tower of the World Trade Center in Downtown surpassed the Empire State Building as the world’s tallest building, as well.

Promo material for the second Waldorf-Astoria, 1933. Credit: Wikipedia

Promo material for the second Waldorf-Astoria, 1933. Credit: Wikipedia

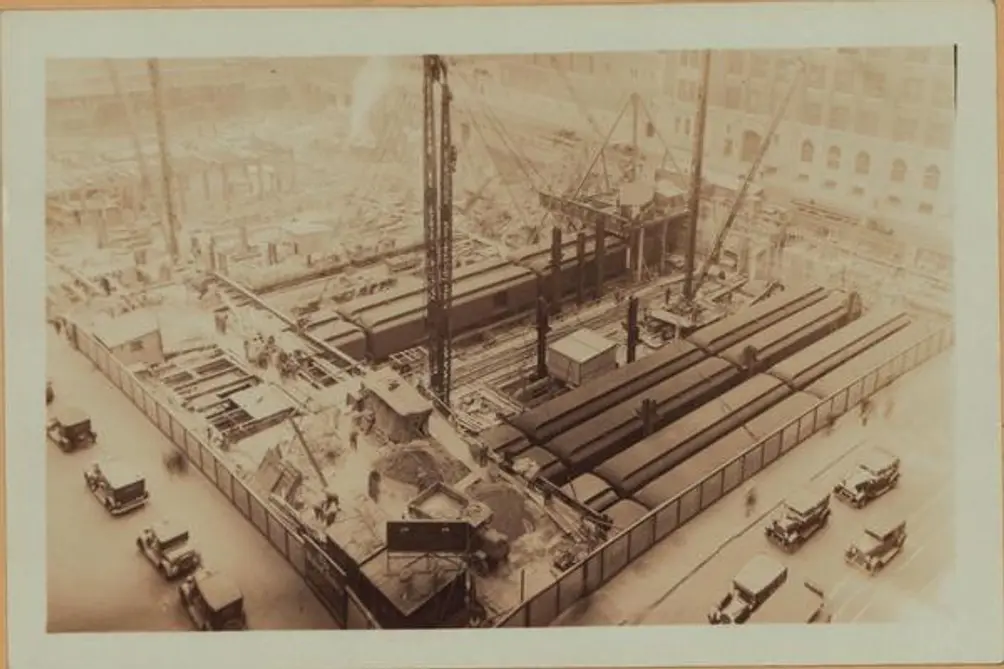

The second Waldorf-Astoria under construction on March 4, 1930. Credit: Percy Loomis Sperr, NYPL

The second Waldorf-Astoria under construction on March 4, 1930. Credit: Percy Loomis Sperr, NYPL

A publicity stunt during construction of the second Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Credit: Needpix

A publicity stunt during construction of the second Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Credit: Needpix

The Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and Park Avenue, looking south. Credit: NYPL

The Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and Park Avenue, looking south. Credit: NYPL

In their sequel to the book quoted earlier in the article, "New York 1930, Architecture and Urbanism Between The Two World Wars," Robert A. M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin and Thomas Mellings gave the following description of the second Waldorf-Astoria:

“The era of skyscraper hotels reached its peak in 1931 with the second Waldorf Astoria, which was designed by Schulze & Weaver, who had co-designed the great Sherry-Netherland Hotel on the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 59th Street in 1927 with Buchman & Kahn.

"With its enormous slab rising from a crenellated base," the authors wrote, "the Waldorf-Astoria, occupying the entire block (80 percent of which was above railroad tracks) between Forty-ninth and Fiftieth streets, Park and Lexington avenues, made a quantum jump in scale and complexity beyond that of the typical skyscraper - whether devoted to offices or hotels - of the interwar era....

"Rejecting virtually all references to the original Waldorf - only the hotel's name and that of the famed Empire Room and Peacock Alley were retained - the new building was an exceptionally elegant exemplar of Modern Classicism, yet it included many suites that used period styles as well as large architectural fragments, such as paneled walls and mantelpieces from historic buildings in England and France.

The design was largely the work of Lloyd Morgan and Louis Rigal, according to the author's. There was drive-though the mid section of the building a siding for those arrived on their private railroad cars.

Just as the original hotel, the new Waldorf was an instant sensation. Its Starlight Roof on Park Avenue had a retractable, open-air roof and the hotel's splendiferous ballroom ensemble could accommodate several thousand people and was the favored locale of the famous Al Smith political dinner, the very social April in Paris Ball and countless events such as the Explorers' Club annual dinner where balut, an African dish of a chicken egg cooked for a few seconds and eaten beaks and claws, and raw lamb's eyes with tough muscle and acid-like liquid were consumed.

The Waldorf-Astoria and Midtown, looking south. Credit: Wurtz Brothers, NYPL

The Waldorf-Astoria and Midtown, looking south. Credit: Wurtz Brothers, NYPL

The domes of the Waldorf-Astoria, looking south. Credit: Underwood & Underwood, NYPL

The domes of the Waldorf-Astoria, looking south. Credit: Underwood & Underwood, NYPL

The elegance of the hotel's Art Deco decorations such as the stainless steel maidens adorning the elevator cabs in the lobby was unmatched.

When the hotel opened on Park Avenue in 1931, it was the tallest in the world and had a radio in every one of its 2,200 suites, in-room dining and 'manufactured weather ' (the term used then for air-conditioning. "It was the most luxurious of its time," notes Katherine Clarke in her 2019 article in The Wall Street Journal. "Almost immediately following its launch, the hotel had to endure the Great Depression. At one point in 1932, it had 1,600 people on its payroll but just 260 registered guests," the article continued.

Many of the property's hotel rooms were modestly sized, yet some suites in "The Towers," the building’s upper portion, were quite spacious, such as the six-bedroom suite occupied by composer Cole Porter. Clarke reported that "his library, designed by Billy Baldwin in 1955, featured tortoise-shell leather walls and brass tube bookshelves." According to "The Waldorf Astoria: America's Gilden Dream," a book by Ware Morehouse III, Frank Sinatra subsequently paid $1 million a year to keep that same suite.

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Douglas Elliman

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Douglas Elliman

The conversion and renovation

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

Conrad Hilton, who at one point also operated the Plaza, eventually acquired the Waldorf-Astoria. His company, Hilton Worldwide Holdings, sold the hotel in 2015 for $1.95 billion to Chinese holding company Anbang which closed it two years later to convert it to 375 condominium apartments and 350 hotel rooms.

The property is currently under the control of Dajia Insurance Group, but Hilton will continue to operate the hotel and the condominiums.

The revamp is being carried out by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and will include a careful restoration of some of the hotel’s interiors — including the West Lounge, formerly known as Peacock Alley, which is located on the first floor; the Grand Ballroom and balconies on the third floor; and the Park Avenue lobby, with its 13 murals and a floor mosaic designed by French artist Louis Rigal — that were designated landmarks in 2017. AD100 Paris-based designer Jean-Louis Deniot is designing the apartments and residential common areas, and Pierre-Yves Rochon is designing the hotel's public spaces.

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

The refurbished hotel will contain 376 hotel rooms, some of the largest in the city, on the lower floors. The condo units will be on floors 12 through 43, with floors 40, 41 and 42 having only two units each. The project's offering plan indicates an average unit size of 1,747 square feet, with apartments ranging from modest studios or guest suite, to a 6,647-square-foot four-bedroom condo that comes with a library and a 3,589-square foot terrace, a 19-foot-long entry foyer that leads past an enclosed, 19-foot-wide kitchen to a 32-foot-wide living/dining room and three bedrooms.

Three more sprawling units — each more than 6,100 square feet, plus terraces — will comprise the penthouses. One of these will have a 46-foot-wide living room, a 16-foot-wide library, a 21-foot-wide entertainment room, a 25-foot-wide dining room and a 29-foot-long kitchen with an island and three bedrooms.

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York (Kate Jordan)

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York (Kate Jordan)

All units are reached via traditional or keyless entry and feature Concierge Closets that allow for private, discreet delivery of packages, dry cleaning, and room service 24 hours a day. Kitchens have custom cabinetry designed by Molteni&C and come outfitted with a full suite of Gaggenau appliances. Primary baths feature floor-to-ceiling honed white Mont Blanc marble slab walls, radiant heated mosaic marble tile floors with a Waldorf Astoria motif, and fixtures and fittings designed exclusively for the residences.

Moreover, residents have the option to purchase their homes fully furnished as part of a turnkey furniture program. This offers a choice of light and dark color palettes and comes with a curated selection of Bang & Olufsen audiovisual products as part of an exclusive partnership. These will include Beolab 8, Beosound 2, Beosound Balance, and Beosound Theatre, and come in Gold Tone and Light Oak and Natural Aluminum and Dark Oak to complement the furniture packages.

Moreover, residents have the option to purchase their homes fully furnished as part of a turnkey furniture program. This offers a choice of light and dark color palettes and comes with a curated selection of Bang & Olufsen audiovisual products as part of an exclusive partnership. These will include Beolab 8, Beosound 2, Beosound Balance, and Beosound Theatre, and come in Gold Tone and Light Oak and Natural Aluminum and Dark Oak to complement the furniture packages.

Light and dark furnishings (Kate Jordan)

Light and dark furnishings (Kate Jordan)

According to the offering plan, condo owners can also license 150 storage bins, 41 wine lockers and 34 parking spots. Storage bins cost $180 to $1,440 for the year; wine lockers run $1,500 a year and parking spots are $6,000 a year.

Park Avenue and the Grand Central Terminal area are undergoing significant change after the city rezoning Vanderbilt Avenue to permit larger buildings, several of which only now being redeveloped.

Despite considerable hoopla about the Hudson Yards mega-development on the far west of Midtown, Rockefeller Center and St. Patrick's Cathedral remain the heart and soul of Manhattan and they are also on 50th Street, Waldorf's street.

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Noe & Associates/The Boundary

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Douglas Elliman

The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria. Credit: Douglas Elliman

Featured Listings

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #2230

$1,875,000

Midtown East | Condominium | Studio, 1 Bath | 563 ft2

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #2230 (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #2033

$2,945,000

Midtown East | Condominium | 1 Bedroom, 1.5 Baths | 888 ft2

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #2033 (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #2910

$6,050,000

Midtown East | Condominium | 2 Bedrooms, 2.5 Baths | 1,705 ft2

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #2910 (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #2310

$9,995,000

Midtown East | Condominium | 3 Bedrooms, 3.5 Baths | 2,335 ft2

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #2310 (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #4205

$18,750,000

Midtown East | Condominium | 4 Bedrooms, 4.5 Baths | 2,971 ft2

Waldorf Astoria Residences New York, #4205 (Douglas Elliman Real Estate)

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Architecture Critic

Carter Horsley

Since 1997, Carter B. Horsley has been the editorial director of CityRealty. He began his journalistic career at The New York Times in 1961 where he spent 26 years as a reporter specializing in real estate & architectural news. In 1987, he became the architecture critic and real estate editor of The New York Post.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.