In a time when so many New York City cultural organizations and low-income neighborhoods are suffering from the economic side effects of COVID, could Transferable Development Rights be an effective Band Aid? Similar to turning water into wine, turning air into revenue seems like a worthy option to explore.

Despite merely being the sale of air, air rights are insanely complicated and highly nuanced. Transferable Development Rights (TDRs) include a number of different types of district designations, different types of purchasing options, as well a multitude of different constraints (geographic, temporal, etc.).

Despite merely being the sale of air, air rights are insanely complicated and highly nuanced. Transferable Development Rights (TDRs) include a number of different types of district designations, different types of purchasing options, as well a multitude of different constraints (geographic, temporal, etc.).

In this article:

Air Rights Summarized

As a brief summary, every lot in Manhattan has a maximum density restriction. Air rights, sometimes referred to as Transferable Development Rights (TDRs), allow landowners to sell any unused development rights to adjacent lots. The new owner of those air rights can build the greater density desired and exceed their "as-of-right" floor area allowances but still must comply with underlying height and setback requirements.The density restrictions, determined by the zoning laws, are known as Floor Area Ratio (FAR), which is the ratio of floor area to lot size. Nyc.gov gives the example that on a 10,000 square foot zoning lot in a district with a maximum FAR of 1.0, the floor area on the zoning lot cannot exceed 10,000 square feet. If a building has a 20,000 square foot zoning lot in a zoning district with a maximum FAR of 5, it cannot exceed 100,000 square feet of floor area.

There are three types of TDR districts: zoning, landmark, and special transfer districts.

Only a handful of experts truly understand all of the intricacies and implications of air rights, but there is the possibility that the sale of air rights could help bridge the gap between NYC’s suffering institutions and communities as a form of pandemic recovery. Building on the article “Understanding the Power of Air Rights,” we now explore air rights to ask if they could be a possible way out of the havoc COVID has wrought.

TDR Districts

Zoning districts

In 2016, the revamped zoning laws stated that any properties that share at least 10 feet of their lot line can purchase the air rights of those adjacent properties. If an adjacent investor buys the air rights of a property they share 10 feet of lot line with, they are then able to purchase the air rights adjacent to the newly acquired property, and so on.To build Central Park Tower on Billionaire’s Row, Extell purchased a whopping total of 563,000 square feet of additional floor area. Extell began by purchasing 130,000 square feet of air rights from the Art Students League of New York in 2006 for $23.1 million, then they bought 6,000 additional square feet of air rights from the League for just under $32 million. Extell then proceeded to acquire more and more air, including 100,000 square feet from The Osborne at 205 West 57th Street, 12,000 square feet from the Saint Thomas Choir School at 202 West 58th Street, 14,290 square feet from 200 West 58th Street, 156,000 square feet from purchasing 1780 Broadway and two adjacent properties properties, and 20,000 square feet from the purchase of a lot on 58th Street and a lot at 232 West 58th Street for a final 20,750 square feet. All for one supertall!

Landmark and Special Transfer Districts

Municipalities can also create unused air rights for the purpose of preserving a landmark building. In 2014, Thomas Church, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 53rd street, transferred their air rights to the building of the supertall 53W53 for $71.2 million.Although potentially incredibly lucrative, landmark transfers are a very bureaucratic and time-consuming process. As a Seton Hall University paper explains, “The New York Landmark Commission requires extensive plans to determine whether the materials, plans, design, and scale are compatible with the landmark. Next, the owners of the landmark and the transferee must appear before the New York Planning Commission for preliminary approval of the transfer. Accompanying this application, site plans for both the sending and receiving lots with a detailed program for continuing maintenance of the landmark, and a report of the Landmark commission detailing the effect of the proposed transfer upon the landmark are required. If the Planning Commission makes a recommendation, the application then goes before the Board of Estimate, which has final authority to grant or deny the application.” This also requires any developer to be interested in the lot in the immediate vicinity.

Special Transfer Districts

The city creates Special Transfer Districts when they want to encourage development in specific locations, for example with the South Street Seaport Subdistrict, the Theater Subdistrict, the Special West Chelsea District, and the Hudson Yards District. The Special Transfer Districts allows the purchaser of the air rights to use their increased FAR within a designated district near the landmark location.

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

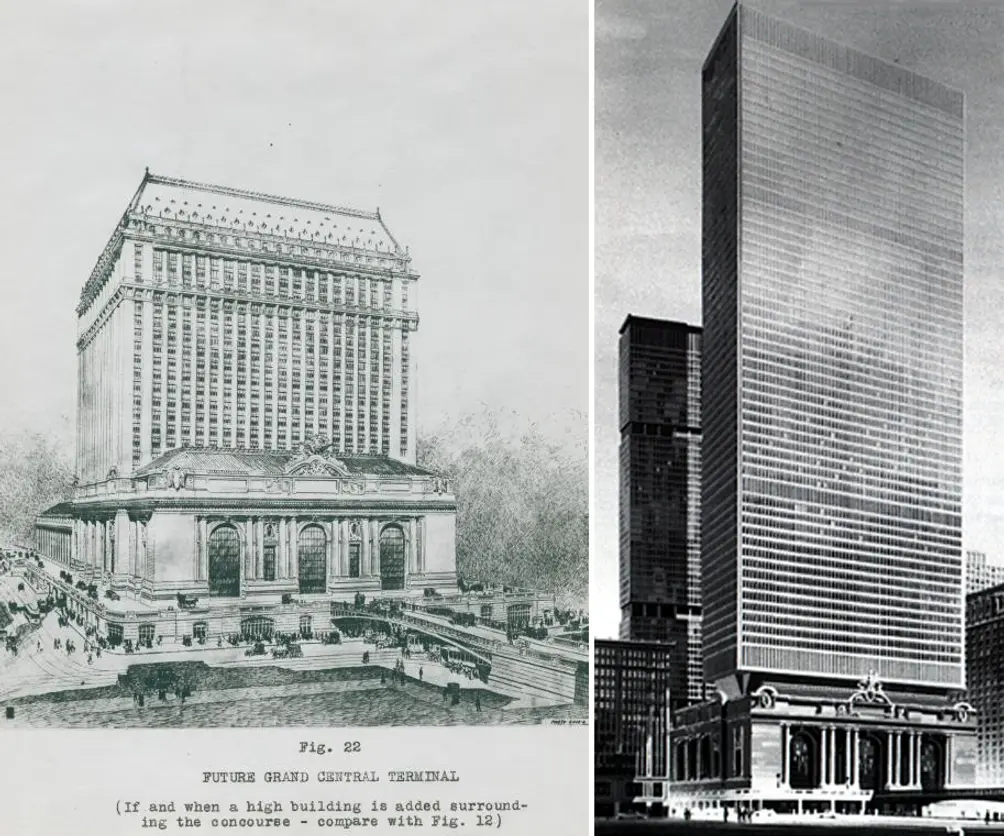

Unbuilt towers proposed above Grand Central Terminal. To preserve the terminal, the unused development rights can be distributed within a special city-created subdistrict

Unbuilt towers proposed above Grand Central Terminal. To preserve the terminal, the unused development rights can be distributed within a special city-created subdistrict

TDR Banks

TDR banks have been a less used but creative way to solve the timing issue in these heavily bureaucratic transactions and have proven successful, such as in the case of the South Street Seaport. In the case of the South Street Seaport, the city created a TDR bank to prevent the destruction of buildings deemed important to the city’s maritime history and to preserve the South Street Seaport Museum that was founded in 1967.TDR banks are third party intermediaries. Typically, the TDR bank is a commercial bank that already holds the historic building’s mortgage. If a developer is interested in a property, the property owner could sell their unused air rights to the banks which hold the rights until the lengthy process is completed and then sells those rights to the developer. This frees up both the buyer and seller in the transaction, the seller to his debt, the buyer to the lengthy transfer process. The bank recoups its return on investment and all three parties benefit.

A municipality can also purchase development rights and hold those rights until there is demand. New York State's Division of Local Government Services says, “Property owners in the receiving districts are eligible to apply for these development rights to increase the densities at which their lands may be developed, and accordingly, may purchase them from the development rights bank. Receipts from the sale must be deposited in a special municipal account 'to be applied against expenditures necessitated by the municipal development rights program.'"

A detailed, long-term study conducted by the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy found “by requiring developers to first purchase from the private market, or by creating a TDR Bank, these newer TDR programs strengthen the market for TDRs and render the programs much more effective.”

The Seton Hall paper states, “By acting as a middleman between buyer and seller, TDR banks fill a critical timing gap that could be the downfall of a TDR program. Government operated TDR banks resolve valuation and marketability problems by setting minimum purchase prices, guaranteeing loans that use TDRs as collateral, and purchasing TDRs outright." Additionally, according to a Louisiana State University Law Center paper, a city could even possibly pool development rights as necessary.

The Seton Hall paper states, “By acting as a middleman between buyer and seller, TDR banks fill a critical timing gap that could be the downfall of a TDR program. Government operated TDR banks resolve valuation and marketability problems by setting minimum purchase prices, guaranteeing loans that use TDRs as collateral, and purchasing TDRs outright." Additionally, according to a Louisiana State University Law Center paper, a city could even possibly pool development rights as necessary.

Additional TDR concepts

Creating affordable housing through air rights

In 2018, Curbed reported that the New York City Housing Authority planned to generate $1 billion from selling over 80 million unused air rights for the purpose of capital repairs.New York City has a Voluntary Inclusionary Housing program to enable developers and owners to build or preserve, more affordable housing in the city. For this program, the affordable housing owner works with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development to generate funding through the creation of development rights, called “inclusionary air rights.” These rights can be transferred to any project in the same community district or within an adjacent community within half a mile of the site. Developers can then purchase development rights for new residential development projects.

A stalled plan that would employ unused development rights of NYCHA's Holmes Towers to build a 50% affordable houisng residential tower (Credit: FXFowle Architects)

A stalled plan that would employ unused development rights of NYCHA's Holmes Towers to build a 50% affordable houisng residential tower (Credit: FXFowle Architects)

Blockchain

Zaheer Allam, an Urban Strategist, suggests blockchain offers many benefits to air rights transactions as it can use smart contracts to automate part of the TDR process, “such as fluctuating prices [by pegging it to strict development ratios in regards to urbanization rate and availability of land],” to add time-sensitive functions, “meaning that one can lose their TDR purchased over a certain period of time” and to increase the efficiency of the process. Allam believes, “The latter could be quite interesting to prevent unhealthy speculation, that tends to push non-wealthy people out from city centers to urban fringes.”Allam also states, “the idea of TDR banks [whether through blockchains, or any other means] can be an interesting exercise if we were to frame it to ensure sustainability [preventing sprawl] and economic inclusivity [ensure that the poor are not pushed on urban fringes].”

Free market

A final option which, admittedly very few discuss, is putting air rights on the open market to be bought and sold and used at will with no restrictions. The great concern of this option is that this would create a capitalistic megacity where supertalls reign supreme killing all street life and architectural diversity in a dark, cavernous zone.Clearly, there are many factors involved and many interests to prioritize. But, as the city looks for creative solutions to raise money, e.g. putting the pied-a-terre tax back on the table yet again, this might be a less controversial and more financially rewarding strategy.

Turning water into wine, turning lemons into lemonade, turning air into revenue

The New York City mayoral race is heating up in many ways and housing is high on the list of most of the candidates as COVID has exacerbated pre-existing problems to a point of near catastrophe. At a recent roundtable on public and private housing, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams announced, “I’m going to look at selling the air rights of NYCHA to local community developers.”Clearly, air rights transfers can generate much needed revenue for small landlords, their tenants, cultural institutions, and other important parts of this diverse city. At this unique point in history, using the lucrative air rights market to create affordable and market-rate housing may be the one way to benefit everyone. Finding a way to do this where all interested parties can work together and not get tied up in bureaucratic knots might be the biggest issue.

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Just complete the info below.

Or call us at (212) 755-5544

Would you like to tour any of these properties?

Contributing Writer

Michelle Sinclair Colman

Michelle writes children's books and also writes articles about architecture, design and real estate. Those two passions came together in Michelle's first children's book, "Urban Babies Wear Black." Michelle has a Master's degree in Sociology from the University of Minnesota and a Master's degree in the Cities Program from the London School of Economics.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.