Photo credit: Winnie Au

Photo credit: Winnie Au

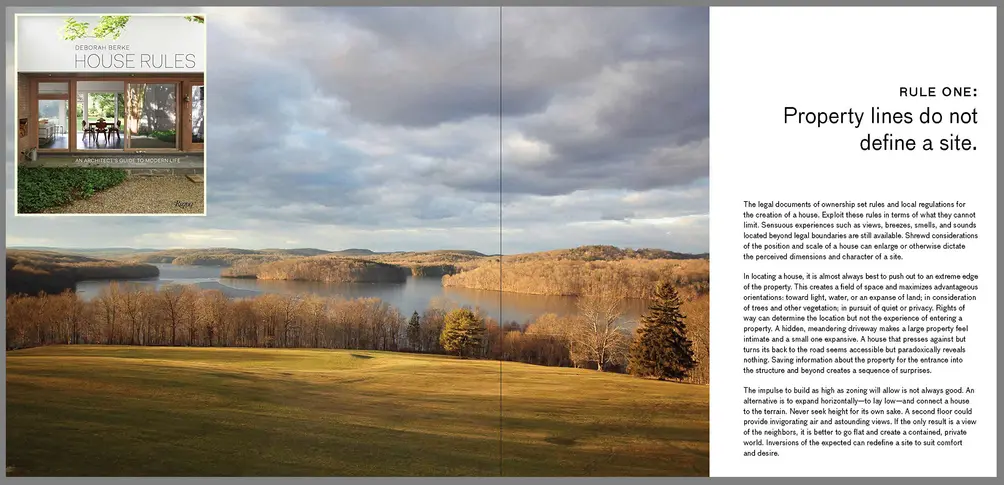

In House Rules, Ms. Berke outlines her eight guiding principles for modern living. The principles range from “Property lines do not define a site” and “Any material can seduce”, to “Circulation does more than connect” and “Reckon with tradition.” Berke, a born and bred New Yorker, believes that those principles become even more important with city living.

Recently, CityRealty spoke to Ms. Berke about her big month ahead and her exciting plans for the future.

Yale Art + Architecture Building / Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects, Courtesy of Gwathmey Siegel

Yale Art + Architecture Building / Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects, Courtesy of Gwathmey Siegel

In this article:

Has Bob Stern given you any tips as he hands the torch over to you?

Yes; Bob has been great. He has been very generous with his time and given me extensive notes. Bob has a highly organized schedule so he’s also shown me the timing of things and how the year unfolds. He’s given me the big picture of the year as opposed to actual decisions, which of course, I will make on my own.

What are you most looking forward to during your tenure as dean?

Dozens and dozens and dozens of things. I want to expand what we teach in the school of architecture. I want to broaden the definition of the discipline and of architecture. I want to increase access so that a more diverse group of people can become architects and/or be knowledgeable about architecture.

I also want to include climate change, sustainability and resiliency into architecture. I want to focus on the overlaps of architecture with public health, public space, and societal well being. And I want to examine the nature of architecture beyond what is currently perceived as its traditional limits.

I think it’s really important to focus on public spaces and landscapes. We have got to go beyond the building as an object. The building is not the sole focus of architecture.

Do starchitect projects help or hurt students' expectations?

Today’s students are much less interested in starchitects than students of a decade ago. Students’ interests are remarkably diverse. They range from what we’ve already been talking about (sustainability and resiliency) to cities, super tall building, new ways of manufacturing, the broad uses of technology and how it can be involved in the structure, aesthetics and fabrication of buildings. Students‘ interests are enormously broad right now; the work of a single starchitect is not motivating them.

What are the most important lessons to teach architecture students beyond what you’ve discussed above?

Having a sense of responsibility but also remembering that architecture is not just problem solving. One solves many problems of many different kinds but architecture cannot be viewed as only problem solving. It is design and creation.

122 CC, the former PS122 in the East Village

122 CC, the former PS122 in the East Village

What is one New York City project you have worked on recently that excites you the most?

I’m excited about 122 CC, the former PS 122 in the East Village. It is a DDC design excellence project. It is a renovation of and addition to an old New York City public school that will house Performance Space, Mabou Mines, Painting Space 122, and AIDS Service Center NYC. We hope it will open by the end of the year. When you walk by it on First Avenue you will see a bit of construction and scaffolding but it’s already looking pretty good.

On to your book, House Rules. How do your 8 principles apply to city living, particularly the rules about property lines and indoor/outdoor spaces?

I am a city person. I was born in New York City and I live here. I am working on another book about living in the city—which probably won’t come out for a few years—but all of the principles in the book apply to urban living.

In terms of property lines, I think it is best defined by New York City and the way townhouses and apartments cut the city up into tiny, tiny grains. Those are property lines. When you get inside and look across street and see the park obliquely, however, the experience of the apartment goes beyond property lines. I live way over by the East River and when the Amtrak trains go over the bridge toward Queens, you can hear the train whistle. All of the the sights and sounds of the city are a part of the urban experience. Property lines are determined by the footprint of the building, one’s experience is not.

In terms of outdoor spaces in the city, the truth of the matter is that very few people have outdoor spaces. We rely on collective outdoor spaces like parks and sidewalks. I love that the New York City Parks Department transforms the tiniest little spaces with benches, planters, chairs and umbrellas. People really sit in and use those spaces; we are so eager to get outside and feel the outside. Rooms can be inside or out and outdoor rooms in urban life tend to be shared with others. In your inside rooms, you throw your windows open wide let whatever comes in come in, noise or dirt, we take it all.

A look inside House Rules

A look inside House Rules

Which of the rules are the most important for creating a livable tiny urban spaces?

The rules are even more important in tiny spaces. I think, in many instances and locations outside New York City, houses have almost gotten too big. I am a great believer of livable tiny spaces. I would say the rule that is the most important is #8: Honor daily life. No matter how small your space is, you need to sleep, you need to eat, you need to maintain your personal hygiene, and you need to be able to have a friend over for a glass of wine. Even if you’re living in one small room, acknowledging that all of those things need to happen will make a livable urban environment and a livable home.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.