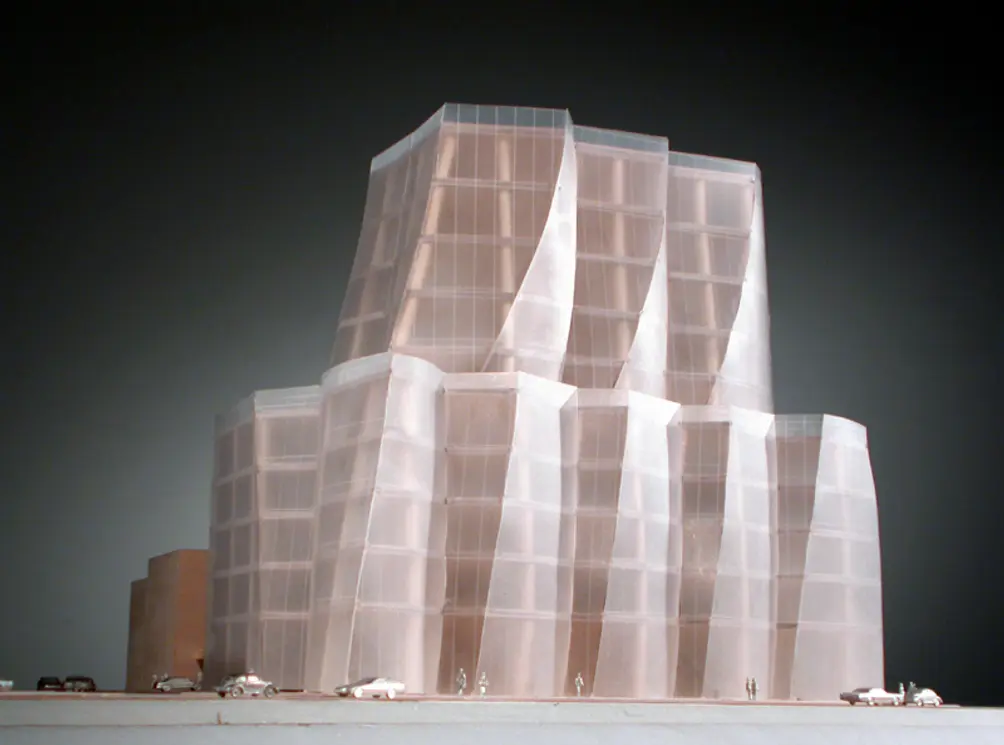

Gehry's shelved Guggenheim project for lower Manhattan's East River waterfront

Gehry's shelved Guggenheim project for lower Manhattan's East River waterfront

In a city defined by its strict grid and anxious vertical rise, Frank O. Gehry’s contributions to New York remain unmistakably his, yet distinctly shaped by the city’s character. Of his two buildings, one channels his signature crushed-steel dynamism into a soaring high-rise, while the other glows and flows alongside the rush of the West Side Highway, translating his iconic motion into a uniquely New York rhythm.

Together, Gehry helped shift the city’s architectural expectations from what towers should do to what they should be.

In this article:

In 2000, Frank Gehry’s first New York commission was the sculptural Condé Nast cafeteria at 4 Times Square, where he transformed a corporate dining hall into a flowing landscape of curved glass partitions, shifting floor levels, and shimmering blue titanium surfaces. The result was a dramatic, almost otherworldly social space that brought Gehry’s signature sense of movement and artistry into the everyday rhythms of office life.

Gehry’s first completed New York building was smaller but just as ambitious in spirit. The IAC Building, finished in 2007 along the West Side Highway, with its billowy sail-like movement and gentle lean, could have been an ordinary office building opting for a rectangular base and predictable window grid. Instead, Gehry introduced a curving glass curtain wall that swirls lightly around interior office floors. From the street, the structure seems to breathe, a striking contrast to the low-slung warehouses and brick loft conversions that surround it, in color, texture, and form.

InterActiveCorp's New York Headquarters

InterActiveCorp's New York Headquarters

The IAC Building demonstrated that even an office headquarters, that most utilitarian form of urban real estate, could carry an architectural identity. New York by Gehry at 8 Spruce showed that a skyscraper could be expressive.

When 8 Spruce Street opened in 2011, it was the tallest residential building in the Western Hemisphere. It instantly altered the skyline. The shimmering 76-story residential tower does not present a conventional façade. Looking like a stainless-steel rectangular skyscraper that was caught in the strong grip of a King Kong on steroids, its skin ripples downward like drapery, catching light differently at every hour. From some angles, it can appear almost liquid.

Rendering of 8 Spruce release while lower Manhattan was still on the mend (Frank O. Gehry Partners)

Rendering of 8 Spruce release while lower Manhattan was still on the mend (Frank O. Gehry Partners)

More than a visual statement, the building also serves multiple functions. At its base is a public school, unusual for a major residential tower, and retail. In combining apartments, civic infrastructure and street-level activity, Gehry asserted that “landmark architecture” should not be removed from everyday urban life, it should house it.

That may be his most subtle revolution in New York: taking sculptural design, something once reserved for cultural temples and museum destinations, and placing it squarely where people live, work and pass frequently without ceremony.

The stainless steel evokes the Chrysler building, the height matches many others in downtown but sitting among the mostly traditional City Hall buildings, 8 Spruce rises high above and makes its presence distinctly heard.

The stainless steel evokes the Chrysler building, the height matches many others in downtown but sitting among the mostly traditional City Hall buildings, 8 Spruce rises high above and makes its presence distinctly heard.

The undulations of the facade aren’t just cosmetic. Where the facade ripples out, the interior walls follow those lines creating small nooks used as bay windows in the condominiums providing panoramic views from those angular projections.

Despite 8 Spruce carrying Gehry’s signature sculptural flair it was shaped by notable compromises. The stainless-steel facade was simplified from a more intricate early design, copper cladding was abandoned for cost and maintenance reasons, and zoning and financial pressures forced a conventional tower under the rippling skin. Additionally, the southern side of the building is flat because the dramatic folds on all four sides would have pushed the tower beyond allowable firecode and property line limits, as well as to provide a straight wall for structural and mechanical reasons. Beyond that, the school podium had to follow strict NYC Department of Education standards and interiors were standardized for efficiency.

In his MasterClass about designing amid the rules and regulations of a specific location, Frank Gehry said, “within all those constraints, I have 15% of freedom to make my art.”

Gehry’s firm was attached to a proposal for a performing-arts center at the World Trade Center site (the Perelman Performing Arts Center / “6 WTC”) but his early designs were later dropped, and the project went forward under REX Architects.

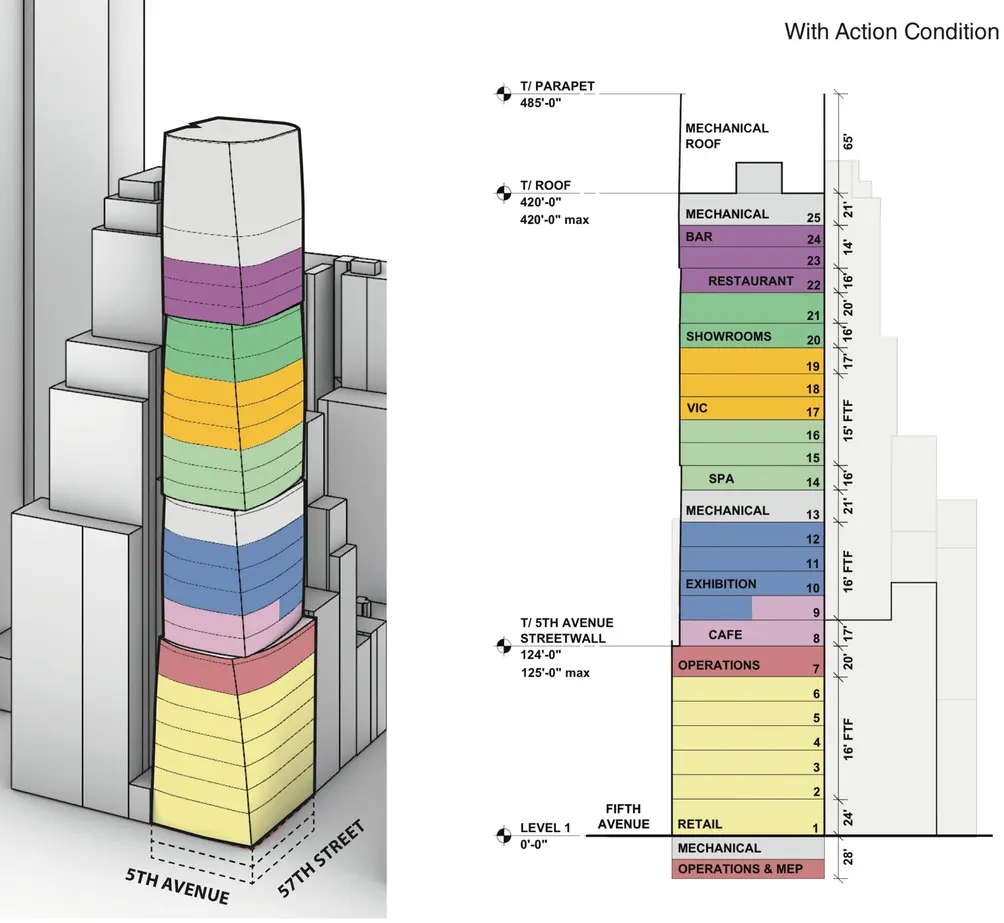

Rumor has it the firm is designing the new 1 East 57th Street flagship: a 485-foot Louis Vuitton tower on Billionaires’ Row. LVMH is redeveloping the existing 20-story building into a taller mixed-use tower. Demolition is underway behind the sculptural scaffolding that mimics the brand’s iconic luggage.

The two realized buildings helped normalize a new vocabulary in New York, one built around geometry, light, and motion. Prior to Gehry, the expectation was that ambitious architectural gestures belonged to museums, performing arts centers or civic monuments. Apartment towers were glass or brick boxes. Office buildings were glass boxes. And, when developers stretched for creativity, they typically were value engineered into glass boxes.

"Prior to Gehry, the expectation was that ambitious architectural gestures belonged to museums, performing arts centers or civic monuments. "

After Gehry, developers began seeking distinction rather than avoidance. Unusual façades, curving lines, and expressive materials were no longer fringe moves reserved for Bilbao, Los Angeles or Berlin. They were legitimate aspirations for Manhattan.

He did not influence lower, less high-budget sectors of the market. And critics have pushed back, arguing that “object buildings”, aka star-driven designs that stand apart visually, can sometimes overpower their neighborhoods rather than integrate into them. Others have suggested that Gehry’s signature folds risk becoming repetitive. Yet those debates only underline the point: Gehry made architecture a public conversation again in a city where many buildings had blended unnoticed into the skyline.

He did not influence lower, less high-budget sectors of the market. And critics have pushed back, arguing that “object buildings”, aka star-driven designs that stand apart visually, can sometimes overpower their neighborhoods rather than integrate into them. Others have suggested that Gehry’s signature folds risk becoming repetitive. Yet those debates only underline the point: Gehry made architecture a public conversation again in a city where many buildings had blended unnoticed into the skyline.

Ad for New York by Gehry | DBOX

Ad for New York by Gehry | DBOX

Perhaps Gehry’s greatest gift to New York is not what he built, but what he allowed others to imagine. That being said, architecture has increasingly pushed back against the excesses of starchitecture, shifting toward environmental responsibility, social purpose, and financial restraint. High-profile projects like Calatrava’s World Trade Center Transit Hub, admired for its dramatic form but criticized for cost overruns and limited practicality, have become warnings. Many cities and clients now favor buildings that prioritize sustainability, community impact, and efficient use of public money rather than sculptural spectacle.

However, by proving that a tall, complex building with a non-traditional silhouette could succeed, financially, politically and visually, he helped loosen the conservatism surrounding urban form in one of the world’s most regulated, historically sensitive cities.

The next generation of architects in New York City now design more freely, with buildings that bend, taper, twist or shimmer, as well buildings that honor pre-war styles without shame. Residents, too, have adjusted their eyes. Where once deviation from the right angle raised suspicion, now it is often welcomed… even expected by some.

Gehry’s two major New York City buildings remain touchstones: expressions of confidence in a city that has never lacked ambition but sometimes lacked permission to dream architecturally. More than a decade later, they stand as reminders that innovation in the skyline does not require a museum entrance or a ticketed event.

As the city has stepped back from pursuing iconic yet expensive architectural statements, Gehry’s presence serves as a reminder of what bold vision can still bring to the city. The many Gehry projects that never made it past the drawing board show how difficult it is to push boundaries here, yet during the starchitecture-driven years of the 2000s and early 2010s the city managed to realize a handful of his works along with several other provocative buildings that continue to inspire today.

Built and unbuilt NYC works by Gehry Partners

Renovated former Condé Nast cafeteria by Frank Gehry | Credit: Jeremy Frechette for Durst Organization

Renovated former Condé Nast cafeteria by Frank Gehry | Credit: Jeremy Frechette for Durst Organization

Frank Gehry’s first New York commission was the sculptural Condé Nast cafeteria at 4 Times Square, where he transformed a corporate dining hall into a flowing landscape of curved glass partitions, shifting floor levels, and shimmering blue titanium surfaces. The result was a dramatic, almost otherworldly social space that brought Gehry’s signature sense of movement and artistry into the everyday rhythms of office life.

Issey Miyake New York | https://us.isseymiyake.com/pages/storesdetail?shop_code=90&view=07-1_stores-detail

Issey Miyake New York | https://us.isseymiyake.com/pages/storesdetail?shop_code=90&view=07-1_stores-detail

Issey Miyake will close its flagship Tribeca store at Hudson and N. Moore on December 12 and reopen in a larger Madison Avenue location in the spring. The Tribeca store, designed by Frank Gehry 24 years ago, reflected the brand’s philosophy. Miyake told Domus in 2001, “I asked Frank because his unique vision translates the organic qualities of nature into a space, creating movement, light, and energy.”

Guggenheim Museum Lower Manhattan

Frank Gehry’s proposed Guggenheim for lower Manhattan reimagined the museum as a sweeping waterfront landmark, a tower and sculptural complex of fractured, curving forms that would hover above the East River and stretch across several piers.

Responding directly to the city’s skyline and the movement of the water, the design combined the rigid verticality of New York skyscrapers with fluid, metallic ribbons that cascaded outward to form vast plazas and esplanades. At its core, the project aimed to create both a cultural engine and a civic destination, offering expansive exhibition halls, public spaces, a theater, and broad riverfront promenades.

Though ultimately shelved, it stood as one of Gehry’s most ambitious visions, an attempt to give Lower Manhattan a defining architectural moment on the scale of Bilbao or even an “Eiffel Tower” for New York

Though ultimately shelved, it stood as one of Gehry’s most ambitious visions, an attempt to give Lower Manhattan a defining architectural moment on the scale of Bilbao or even an “Eiffel Tower” for New York

New York Times Headquarters Competition Design Entry

The New York Times Headquarters design competition, held around 2000, was won by Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW), beating out firms like Foster + Partners, Cesar Pelli, and Frank Gehry for the iconic 52-story tower featuring a distinctive double-skin facade with white ceramic rods, transparency, and energy efficiency. Piano's design emphasized lightness and interaction, contrasting typical office towers with open workspaces and a public-facing lobby with an internal garden, aiming to embody the newspaper's commitment to open information.

Pacific Park master plan, formerly Atlantic Yards

Pacific Park, formerly Atlantic Yards, is a mixed-use development by Forest City Ratner in Brooklyn, spanning 22 acres near Prospect Heights, Downtown Brooklyn, Park Slope, and Fort Greene, with 8.4 acres over a Long Island Railroad yard. The project includes 17 high-rises and the Barclays Center, which opened in 2012. Overseen by the Empire State Development Corporation, it has faced delays, with completion pushed from 2025 to 2035, and features the world’s tallest modular apartment building, 461 Dean, opened in 2016.

Brooklyn Atlantic Yards Nets Arena

Barclays Center, conceived by Bruce Ratner of Forest City Ratner, is a multi-purpose arena in Brooklyn, home to the NBA’s Brooklyn Nets and the WNBA’s New York Liberty. Opened on September 28, 2012, it hosts sports, concerts, and other events as part of the Pacific Park complex near the Atlantic Avenue subway and LIRR stations. The arena, named for British bank Barclays, is owned by the State of New York through the Brooklyn Arena Local Development Corporation, leased by Brooklyn Event Center LLC, and operated by Joseph Tsai’s BSE Global.

IAC Building

The IAC Building, completed in 2007 at 555 West 18th Street in Chelsea, Manhattan, is Frank Gehry’s first full-building design in New York City and serves as the headquarters for media company IAC. The 10-story structure features a striking glass façade with sail-like “cell” units that give the impression of two towering stories, blending sculptural drama with functional office space designed for collaboration. Originally intended to be clad in wrinkled titanium, the smooth glass exterior was chosen at the request of IAC CEO Barry Diller. At the time, its lobby featured the world’s largest high-definition screen, and in 2023, IAC purchased the land beneath the building for $80 million.

WTC Performing Arts Center

The Perelman Performing Arts Center, or PAC NYC, is a multi-venue performing arts center at the northeast corner of the World Trade Center complex in Lower Manhattan. Named for Ronald Perelman, who donated $75 million, the center was first proposed in 2004 and underwent multiple design changes before architects Joshua Ramus and Davis Brody Bond, with structural engineer Magnusson Klemencic Associates, completed it. Construction began underground in 2017 and above ground in 2020, and the 90,000-square-foot facility opened on September 13, 2023.

New York by Gehry, 8 Spruce Street

8 Spruce, formerly Beekman Tower and New York by Gehry, is a 76-story, 870-foot residential skyscraper in Manhattan’s Financial District, designed by Frank Gehry and developed by Forest City Ratner. Opened in February 2011 as the tallest residential tower in the Western Hemisphere, it houses 899 apartments above a base that includes a school, hospital, retail space, and parking.

Louis Vuitton, 1 East 57th Street

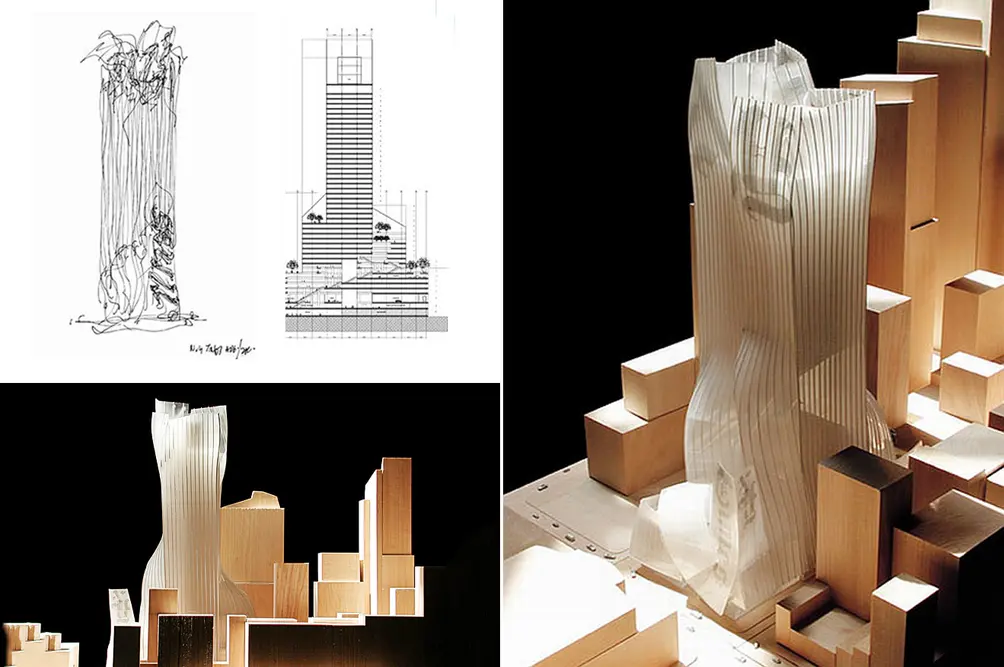

Drawings for LVMH's 1 East 57th Street look Gehry-esque enough

Drawings for LVMH's 1 East 57th Street look Gehry-esque enough

1 East 57th Street flagship is a 485-foot Louis Vuitton tower on Billionaires’ Row. LVMH is adding five stories to the existing 20-story building, and interior demolition is underway behind a sculptural scaffolding that mimics the brand’s iconic luggage.

Contributing Writer

Michelle Sinclair Colman

Michelle writes children's books and also writes articles about architecture, design and real estate. Those two passions came together in Michelle's first children's book, "Urban Babies Wear Black." Michelle has a Master's degree in Sociology from the University of Minnesota and a Master's degree in the Cities Program from the London School of Economics.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.

6sqft delivers the latest on real estate, architecture, and design, straight from New York City.